When LGBTQ+ spaces are under attack, can we thrive and be safe in the spaces around us? Tom Gilbert explores this, taking inspiration from Dan Glass’ Queer Footprints event at the London LGBTQ+ Community Centre.

We queers have a certain sensibility for space. For us, everyday spaces can mark the difference between safety and danger, acceptance and rejection, life or death. Queer identity is shaped by the knowledge that certain spaces are meant for us, and certain spaces are not. It is no surprise for instance, that alcoholism and addiction are so prevalent in the queer community when most spaces we are allowed to freely self-express are centred around drugs and alcohol.

That sensibility to space was briefly shared by our cis-het counterparts in the Covid-19 pandemic. For some, it was the first glimpse of what it’s like to be unsafe in a public place. You would think that this would bring home the need to protect our spaces. However, the lockdowns in fact sped up the ongoing process of queer venue closure, something already eating its way through London’s queer scene.

A report by UCL found that nearly 58% of all queer venues in London had shut between 2006 and 2017. That’s a drop from 121 to 51 in the space of just 5 years. While research into the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the queer community conducted by the London LGBTQ+ Community Centre found that 85% of respondees felt there were too few LGBTQ+ spaces left in London.

The queer community in the UK has been particularly hard hit by this erosion of space because our government refuses to offer the same protection for our clubs and venues as other European countries. In Berlin, Germany for instance, clubs have protected status as cultural venues, affording them tax exemptions. This has prevented queer venues closing in the face of Covid-19, fuel shortages and rent increases.

How then, when our spaces are under attack, can queer people thrive and be safe in the spaces around us? And if queerness is, as bell hooks describes, “the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create…to thrive to live” then what does it mean to queer a space? Enter Dan Glass and his latest project ‘Queer Footprints’.

In eight sections mapping out different areas of London, Dan extends the invitation to take up space, to recognise and understand the latent queer history in London’s streets and to take ownership of them. Central to Dan’s work is an awareness of spaces as a catalyst for events and movements. He describes this as the multiplier effect. Those collisions, interactions, and exchanges that only certain spaces can facilitate, multiply in power and significance when they become concrete events and even wider movements.

In this way, Dan’s guide interweaves the events which we undergo in our personal lives, which may not seem significant on their own, with wider national change. We begin the work of queering a space when we initiate those discussions, interactions, and collisions.

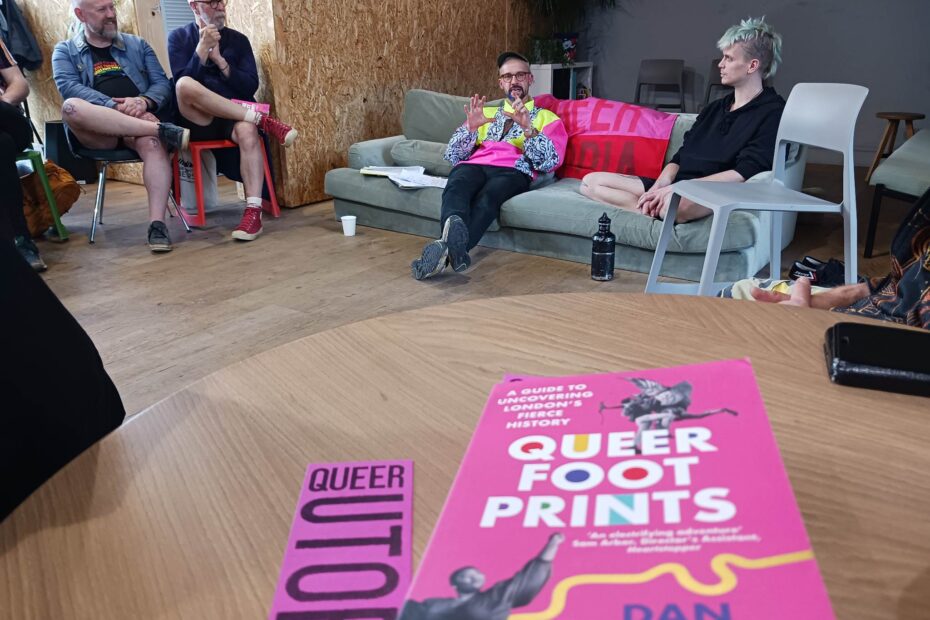

Take the recent Queer Footprints workshop co-hosted by Lip Wieckowski at Bankside’s London LGBTQ+ Community Centre. True to both the philosophy of the Centre and Dan’s work, the workshop encouraged interaction, engagement, and discussion. At one stage, Dan asked the audience to go round and discuss each of our own personal queer icons and why they inspired us. This kickstarted the excited sharing of personal anecdotes, queer experiences, and debate. Members of the group were empowered to bounce ideas off one another and build from each other’s shared interests and experiences. – and like that, the multiplier effect takes hold.

The group discussion led to shared learning, which led to affirmation of our history and queer identity, the effects of which will no doubt translate into further events and concrete activism. Personally, the conversation I had with my neighbour around trans housing justice and Gendered Intelligence, a trans-led organisation that encourages understanding of gender diversity, highlighted to me the urgency of trans rights and activism. This in turn gave me space to reflect on my own relationship to my queerness and how I could be a better ally to people across my community.

Conversations like this are made possible by a space like the London LGBTQ+ Community Centre, which offers a huge range of events for those from across the queer spectrum. Coming up is a day to celebrate Queer Women and Non-Binary people. Events like these invite queer interaction, discussion, and solidarity, which in turn equip our community with the resources to engage with activism, self-discovery and community going forward.

Dan’s work, alongside the work of spaces like the London LGBTQ+ Community Centre, tap into an underlying creative power in queerness. When we’re “at odds with everything around”, then one has no choice but to rebuild and create one’s own spaces and power. The spaces and places which catalyse such discussions and interactions safely, like the London LGBTQ+ Community Centre, are essential for our community to thrive.

There is and always will be, great power in place.

This article was written by Tom Gilbert, a volunteer at the London LGBTQ+ Community Centre. Read more of their work on Linktree. All views expressed are by the author.